When Skates Became Drums: The Night Hamilton, Wylie & Browning Shook The Ice

Stars on Ice has always been the rare touring production that treats figure skating like live theater rather than a scorecard exercise. Founded in the mid-1980s with Scott Hamilton as one of its driving forces, the show gave Olympic champions a second act—one built on personality, lighting, music, and crowd connection instead of judges’ marks. By the mid-1990s, the tour had become a creative playground. Skaters weren’t bound by competition rules; they could experiment. Out of that freedom came one of the most inventive group numbers in skating history: “Five Minutes for Icing,” a routine that turned the rink itself into an instrument.

The concept was brilliantly simple but technically bold. Instead of skating quietly over prerecorded music, the performers attached microphones to their skates. The steel blades biting into ice became percussion. Every edge change, toe pick strike, and stop created sound amplified through the arena speakers. The audience didn’t just watch footwork—they heard it. What normally fades into background noise suddenly became the backbone of the performance. The rink wasn’t just a surface anymore; it was a drum.

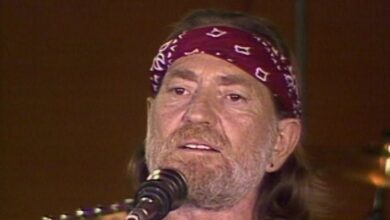

The U.S. version that fans most associate with the routine featured Scott Hamilton, Paul Wylie, and Kurt Browning. Each brought a distinct flavor. Hamilton had showman timing and charisma that could ignite a crowd instantly. Wylie carried crisp musicality and dancer-like precision. Browning delivered footwork so fast and intricate that even non-skaters could sense its difficulty. Together, they created something that felt less like a trio number and more like a playful duel—three masters challenging each other in escalating bursts of rhythm.

What makes “Five Minutes for Icing” stand out is that it never tries to be elegant in the traditional figure skating sense. There are no grand lifts or sweeping romantic poses. Instead, the choreography focuses on power, speed, and rhythmic attack. The blades chatter, scrape, and snap against the ice in tightly controlled patterns. It feels almost rebellious—skating stripped of polish and presented in raw form. The sound of effort becomes the music.

The structure of the routine is carefully designed even if it feels spontaneous. It begins with individual showcases, each skater stepping forward to establish his rhythmic voice. Then the exchanges quicken. Short sequences become longer, sharper, more competitive. By the final moments, all three are pushing tempo and complexity, feeding off the energy of the arena. It resembles a jazz jam session or a tap-dance battle, except the stage is frozen and unforgiving.

Part of the reason the number became legendary is timing. In the 1990s, figure skating enjoyed massive popularity, and Stars on Ice arenas were packed. Audiences were eager to see their champions in a relaxed, creative setting. “Five Minutes for Icing” offered something entirely new: a performance where difficulty was audible. Even viewers unfamiliar with edge terminology could hear which sequences were sharper, louder, faster. The risk felt immediate and real.

There were variations of the routine over the years, sometimes featuring different lineups, but the core concept remained intact. The microphones stayed. The rhythmic call-and-response remained. And the sense of friendly rivalry remained central. The routine proved flexible enough to adapt while retaining its identity, which is one reason it endured rather than fading into nostalgia.

What truly elevates it historically is influence. After this routine gained popularity, other touring productions began experimenting more openly with amplified blade sound and rhythm-based choreography. “Five Minutes for Icing” didn’t just entertain; it expanded what audiences thought skating performances could include. It blurred the line between sport and percussion theater.

Watching the performance from start to finish, the first surprise is the soundscape. The amplified edges are crisp and percussive, almost startling at first. Then the rhythm patterns begin to organize into phrases. You realize the skaters aren’t just making noise—they are composing in motion. Each strike is placed deliberately. The ice becomes both instrument and dance partner, responding with texture and resonance.

In broadcast-style recordings, close camera angles reveal how much technical control underlies the apparent spontaneity. Every stomp-like accent must land on a controlled edge. Every quick step sequence happens at speed while maintaining spacing with two other elite skaters. The illusion of a casual rhythm battle hides years of discipline. It is choreography disguised as improvisation.

Comparisons to rhythm stage productions like STOMP are inevitable. Both forms take everyday impact sounds and elevate them into performance art. The difference is that skaters are working on a slick surface where balance is constantly at risk. A missed beat in tap dance might look messy. A missed beat on ice can mean a fall. That underlying danger adds tension to every exchange.

Tap dance provides another clear parallel. Masters of rhythm create narrative purely through timing and impact. “Five Minutes for Icing” achieves something similar but through blades carving arcs instead of shoes striking wood. The crowd reacts not just to speed, but to phrasing—the way a sequence accelerates, pauses, and explodes again.

What keeps this routine alive in skating culture decades later is its clarity. It doesn’t rely on nostalgia alone. The idea is strong enough to stand on its own: take the hidden sound of skating and turn it into the headline. That creative shift feels fresh even now.

No one claims it was the only great Stars on Ice number. But it was different. It made audiences lean forward. It made them listen. It revealed a side of elite skating rarely showcased in competition—the rhythmic athleticism hidden in every edge.

In the end, “Five Minutes for Icing” wasn’t just a clever trick with microphones. It was a reminder that skating is more than silent grace. It has texture, grit, and pulse. And for five unforgettable minutes, three champions turned frozen water into thunder.