Ilia Malinin — Born Into Olympic Ice, Raised Without Pressure, And Built By Choice

Ilia Malinin’s story doesn’t begin with sudden fame or viral clips—it begins inside a family where elite skating was already a lived reality. He was born into a household shaped by Olympic discipline, early mornings, and the quiet pressure of knowing exactly how demanding the sport can be. His parents, Tatiana Malinina and Roman Skorniakov, weren’t distant legends from another era; they were people who had already paid the physical and emotional cost of skating at the highest level. That background makes Ilia’s rise feel less like destiny and more like something that had to be chosen.

Both of Malinin’s parents were born in Russia and trained within the demanding Soviet-era skating system. Tatiana Malinina grew up in Novosibirsk, deep in Siberia, while Roman Skorniakov was raised in Sverdlovsk, an industrial city with a strong sporting culture. Their early careers were shaped by discipline, limited resources, and constant competition. Eventually, both chose to represent Uzbekistan internationally, a decision that would define their Olympic paths and place them among the country’s most prominent figure skating representatives on the world stage.

Malinina and Skorniakov competed for Uzbekistan at two Winter Olympics, appearing in both the 1998 Nagano Games and the 2002 Salt Lake City Games. Beyond Olympic appearances, Malinina carved out a particularly historic résumé. She became the first Four Continents Champion in 1999 and the first skater representing Uzbekistan to medal at major ISU championships and Grand Prix events. Her achievements weren’t symbolic—they were foundational, placing Uzbekistan firmly on the figure skating map during a transitional era for the sport.

After retiring from competitive skating, both parents transitioned into coaching, carrying their experience forward rather than leaving the rink behind. Their decision to move to the United States was driven by practical concerns, including deteriorating training conditions in Tashkent. Settling in Virginia, they rebuilt their lives around coaching, stability, and family. In January 2000, they married, beginning a new chapter that blended professional skating knowledge with everyday domestic life far from Olympic spotlight.

Ilia Malinin was born in December 2004 in Fairfax, Virginia, into this environment—but notably, skating was not forced on him. In fact, his parents were openly resistant to the idea. Having lived the grind of elite competition themselves, they understood the sacrifices too well. They wanted something easier for their children, something less consuming. Skating, to them, wasn’t romantic—it was relentless. That awareness shaped how Ilia’s early years unfolded.

For a time, skating was simply a place Ilia spent afternoons after school while his parents coached other athletes. He wasn’t treated as a prodigy or groomed for stardom. He skated casually, without intense expectations or specialized focus. His parents didn’t even take his training seriously at first, seeing it more as structured activity than a future career. That distance may have been intentional, a way to let interest develop naturally rather than under pressure.

Everything shifted gradually rather than suddenly. Ilia qualified for the U.S. Championships at the juvenile level when he was just nine years old, despite training only a few days a week. That moment marked the first clear signal that something unusual was emerging. Even then, his parents remained cautious. Talent alone wasn’t enough to convince them—because they knew exactly how much more the sport would demand if he truly committed.

The real turning point came when Ilia landed his first quadruple jump at age thirteen. It wasn’t just impressive—it was unexpected. His parents later described the moment with surprise rather than pride, realizing he was “surprisingly good.” That reaction says a lot. This wasn’t a child being pushed by ambition; it was a family being forced to reassess what was possible when raw ability met genuine interest and fearlessness.

Ilia himself has been open about the fact that skating wasn’t his original dream. He imagined becoming a soccer player, but practical realities intervened. His parents’ schedules didn’t allow for soccer training, and skating gradually filled that space. What began as convenience turned into commitment, not through pressure, but through momentum. Skating didn’t replace another dream—it became one organically.

As his skills escalated, Ilia earned the nickname “Quad God,” a label that reflects both his technical dominance and his willingness to attempt what others avoided. In 2022, he made history by becoming the first person to land the quadruple Axel—four and a half rotations—in competition. It wasn’t just a milestone; it was a redefinition of what was considered achievable within figure skating’s physical limits.

That achievement didn’t occur in isolation. It was the product of years spent around knowledge, caution, and restraint. Unlike many prodigies, Ilia grew up hearing firsthand about injuries, burnout, and disappointment. His parents didn’t glorify the sport—they explained it. That grounding may be one reason he approaches risk with such clarity, pushing boundaries without appearing reckless.

By the time he reached the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, Ilia had already reshaped men’s skating. Winning Olympic gold in the team event solidified his place not just as a technical innovator, but as a reliable competitor under pressure. For a skater raised by two Olympians, the moment carried layered meaning—achievement without illusion, success without surprise.

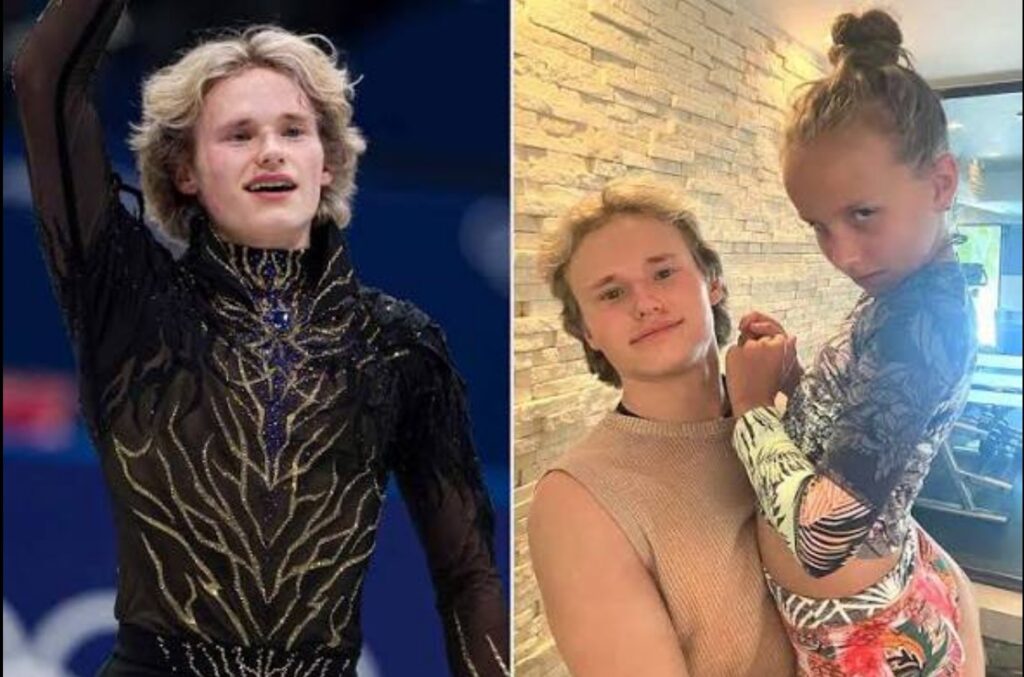

The Malinin family story also includes Ilia’s younger sister, Elli Beatrice, known as Liza, who followed her brother onto the ice. She is a nationally ranked junior skater, continuing the family’s connection to the sport. Yet even with two children skating, the household dynamic remains notably restrained. There is pride, but little spectacle. Achievement is acknowledged, not dramatized.

One of the most telling details about Tatiana Malinina is that she often avoids watching her son compete live. The anxiety is too intense. After years of understanding every possible way a skate can go wrong, watching becomes unbearable. That detail underscores the family’s emotional realism. This isn’t a fairy tale about legacy—it’s a human story about knowledge, love, and restraint.

In the end, Ilia Malinin’s rise isn’t defined by inheritance alone. It’s defined by choice—his choice to pursue skating despite his parents’ reluctance, and his parents’ choice to support him once it became clear he was different. That balance between experience and freedom, caution and courage, may be the quiet force behind his historic career.