Why the Budweiser Clydesdales Are Never Alone — and Why the Dalmatian Still Matters

The Budweiser Clydesdales have always been bigger than a brand asset. From the start, they were designed to feel like living Americana—massive, calm, ceremonial, and slightly unreal, as if they’d stepped out of an older version of the country. Their first appearances weren’t framed as “marketing content” so much as public theater: a hitch of enormous horses, polished harness, iconic wagon, and a pace that forces a crowd to slow down and watch. That slow-down effect is part of the magic. In a world that moves fast, the Clydesdales create a moment that moves on their terms—measured, patient, unbothered—like a tradition you can’t scroll past.

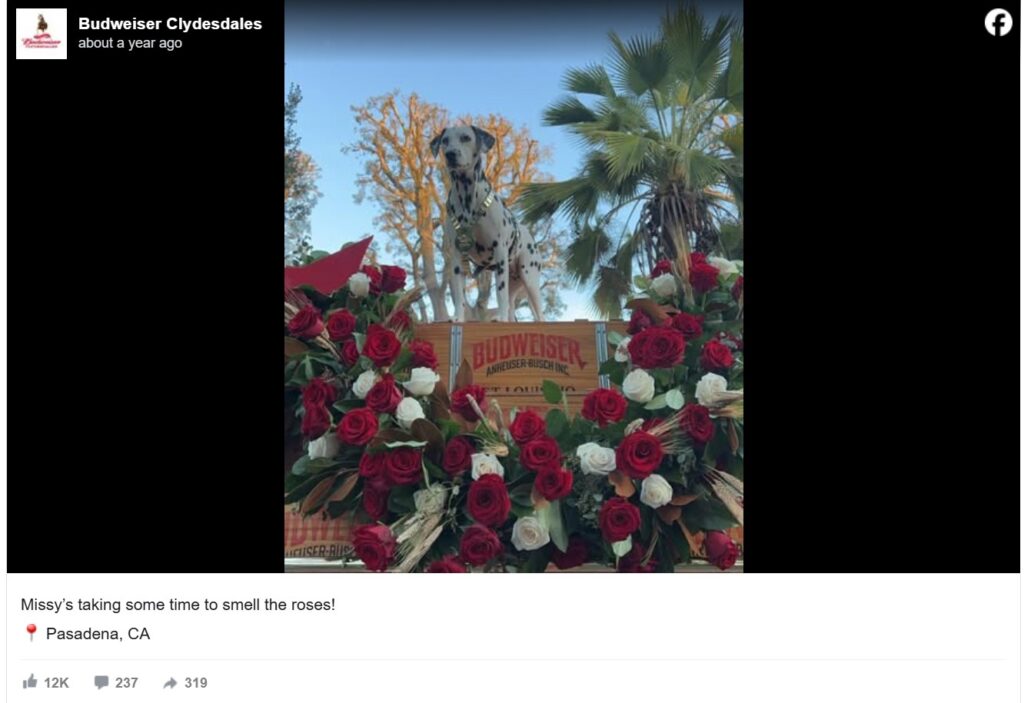

That’s why the Dalmatian matters. The dog isn’t there to decorate the wagon like a cute accessory. It changes the image’s meaning by adding a second layer: not just spectacle, but companionship; not just strength, but alertness. It’s also a visual that taps into something older than TV commercials—animals doing a job together, moving as a unit, a team with different roles. Even people who don’t know the history sense that the dog “belongs” there. The posture is confident. The placement is intentional. The pairing feels inherited, not invented, which is exactly why it reads as tradition instead of a one-off creative choice.

The story gets more interesting when you trace where that bond actually comes from. Long before Budweiser became famous for Super Bowl ads, Dalmatians were widely associated with horses and wagons as “coach dogs,” running alongside carriages, keeping close to the wheels, and serving as guardians and companions for horses on the move. That heritage is not folklore; it’s a documented role that followed the breed into several working environments, including firehouses, where Dalmatians ran with horse-drawn fire wagons and became part of the public image of the team. The point isn’t that every Dalmatian was a heroic protector. The point is that the pairing—horse plus spotted dog—already existed as a recognizable working partnership in the public imagination.

Budweiser stepped into that existing symbolism at exactly the right time. After Prohibition ended, the company leaned into public celebration, and the Clydesdales became a centerpiece of that renewed identity—an emblem of return, continuity, and confidence. Over the years, the horses were shown in parades, ceremonies, and promotional appearances that treated them almost like national mascots. The brand didn’t need a complicated message; it needed a feeling, and the feeling was “heritage in motion.” The Clydesdales delivered that instantly. But as iconic as the horses were, the image still had room to become warmer, more human, more emotionally readable—something that could feel intimate even at a distance.

That’s where the Dalmatian enters the Budweiser timeline as a specific, named tradition rather than a general visual motif. Budweiser’s own historical summaries point to 1950 as the moment the Clydesdales “received” a Dalmatian mascot, turning the dog into a consistent companion presence rather than an occasional flourish. The effect was immediate: the hitch looked less like a formal parade unit and more like a traveling household—giant working animals with a smaller working animal perched in the center of it all. That contrast makes the entire scene more approachable. The horses remain awe-inspiring, but the dog makes the tableau feel like a story.

Once the dog becomes part of the hitch, the image starts doing two jobs at once. On one level, it’s still pageantry: gleaming wagon, powerful horses, handlers in polished attire, a slow-moving procession that feels ceremonial. On another level, it becomes narrative. The dog suggests watchfulness and loyalty. It suggests the team is alive and aware, not just a rolling set piece. The Dalmatian sitting on the wagon looks like a guardian on duty—calm, present, and ready. And because the dog is smaller and more emotionally legible than a horse, it acts like a bridge for the audience. People project onto the dog first, then they feel connected to the horses.

That projection is what allowed the Budweiser animal universe to explode into pop culture over time. The Clydesdales aren’t merely “famous horses.” They became characters—recurring symbols that could carry themes like perseverance, reunion, protection, and pride. As advertising shifted into the era of big cultural moments, the hitch adapted without losing its core identity. The horses remained timeless; the storytelling around them modernized. That’s why Budweiser’s animal storytelling has had such endurance: it can plug into contemporary emotion while still feeling like an old tradition. The Dalmatian fits that approach perfectly, because it looks like it belongs to history even when it’s filmed in ultra-modern, cinematic style.

There’s also a practical side that deepens the legend. Budweiser’s current official descriptions still emphasize the “coach dog” heritage—Dalmatians historically running between carriage wheels and acting as companions to horses—which is the brand’s way of saying the pairing isn’t random. In earlier eras of horse-drawn deliveries, guard-and-companion dogs were part of the ecosystem of movement and cargo. The mythic version is “the dog protected the team.” The realistic version is “the dog helped—by presence, alertness, and familiarity with horses.” Either way, the image lands because it’s rooted in roles animals genuinely played, not solely in the desire to sell a product.

That historical rooting matters because it changes the emotional read of modern Budweiser content. When viewers see a Dalmatian near the hitch today, it doesn’t just register as “cute.” It registers as “continuity.” It says the brand is carrying forward a little piece of working history—horse culture, wagon culture, the ceremonial display of old logistics in a modern world. It’s nostalgia, but not the flimsy kind. It’s nostalgia with a job description. And when something has a job description, people trust it more. They feel like they’re seeing a tradition, not a gimmick.

Even the way the Dalmatian is positioned reinforces that trust. The dog isn’t typically shown darting around as comic relief. It’s presented as composed, trained, and steady—like it’s part of the uniform of the hitch. That matters because Budweiser’s whole Clydesdale identity is built on calm control. The horses are powerful, yet gentle. The handlers are precise, yet unshowy. The wagon is ornate, yet functional. A frantic dog would break the spell. A composed Dalmatian strengthens it. The entire scene becomes a single visual sentence: strength, steadiness, tradition, and watchful companionship.

Modern audiences, of course, also bring modern questions—especially around animal welfare and how these traditions are maintained responsibly. Over the last few years, public scrutiny around animal treatment has become part of the broader story of iconic animal branding, and Budweiser has had to answer that attention directly. Reporting has noted the company’s moves around welfare standards and practices, including changes in how certain procedures are handled, and the broader claim of prioritizing animal safety. This matters because it shows something important about the endurance of the Clydesdales-and-Dalmatian pairing: to keep a tradition alive in the modern era, it has to be defensible—not just beautiful.

That tension—between tradition and modern expectation—is part of why the pairing hasn’t faded. Budweiser could have quietly retired the Dalmatian presence and many casual viewers wouldn’t notice right away. But the brand seems to understand that certain symbols are load-bearing. Remove them and the image loses its depth. The hitch becomes a beautiful parade unit, but it becomes less of a “world.” The Dalmatian is one of those small details that tells the audience: this is not a one-time performance; it’s a traveling ritual with history behind it. The dog signals lineage, and lineage is what turns a brand icon into something people talk about like folklore.

There’s also a reason the pairing keeps working across generations: it’s instantly readable. Even if you know nothing about coach dogs, nothing about firehouse history, nothing about beer wagons, you still understand what you’re seeing. Big protectors. Small guardian. A team moving together. The dog is the emotional “handle” that lets people hold onto the image. The horses are awe; the dog is intimacy. Put them together and you get an icon that can live in parades, commercials, social media clips, and even fan theories about “what it all means.” That flexibility is rare, and it’s why the same pairing can stay powerful for decades without needing to be reinvented.

In the end, the reason this pairing still exists today is surprisingly simple: it’s a true symbol that performs like a story. Historically, Dalmatians were linked to horse movement and carriage life; culturally, they became linked to protection, vigilance, and teamwork; and visually, they complete the Clydesdale tableau in a way that feels inevitable rather than designed. Budweiser didn’t just keep a dog around for charm. It kept a piece of visual history that audiences already understood at a gut level. Once you learn that, the image really does stop being “cute.” It becomes a shorthand for trust, duty, and continuity—exactly the kind of meaning that doesn’t fade, because it’s never been only about marketing in the first place.